Last month, we witnessed remotely, thanks to citizen reporting, the forced and violent evictions of women, children, families and workers occurring in a part of Agbogbloshie, “Old Fadama”, a neighbourhood of Ghana’s capital city Accra. We read estimates of 15,000-20,000 displaced and that children are now sleeping on the roadside and bus stations.

Agbogbloshie is located around the banks of the Korle Lagoon and close by to Accra’s Central Business District. The majority of its inhabitants are from the northern regions of Ghana who have lived, worked and built a life for themselves on the land.

These evictions were carried out following floods, and there is a history of conflict and negotiation between landowners, the city and residents. Land matters are always complex and rarely fully understood from afar.

So what does this have to do with electronic waste?

We feel concerned that in some way the clearance of Agbogbloshie has been made easier by its depiction in the media. Thanks to the media, Agbogbloshie became a global symbol for what is alleged to be a vast and growing environmental problem: the export of e-waste from the developed world to West Africa. Heather Agyepong speaks about the Western “gaze” here.

Yet in recent years, academic and UN-sponsored research has shown that the problem is far more complex – and, in all respects, smaller – than what is being depicted. According to the most comprehensive survey undertaken of Ghana’s electronics imports, 90% of the electronics imported into the country were new, used and working, or used and repairable. The 10% remaining – around 21,000 tons – would amount to less than .05% of the total e-waste generated globally in 2014, as measured by the UN’s Solving the E-Waste Problem initiative [STEP]. Read more from journalist Adam Minter.

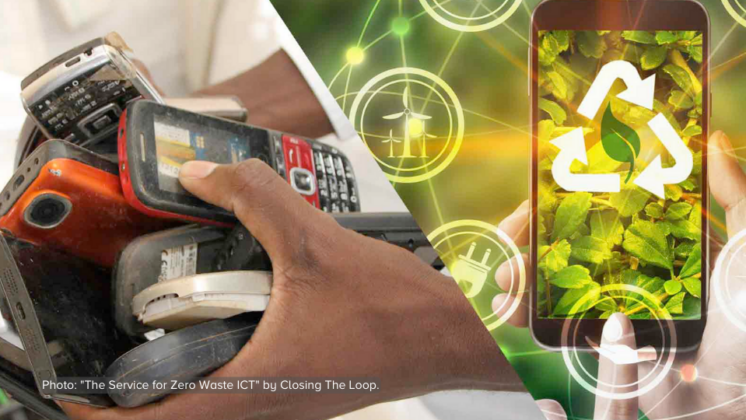

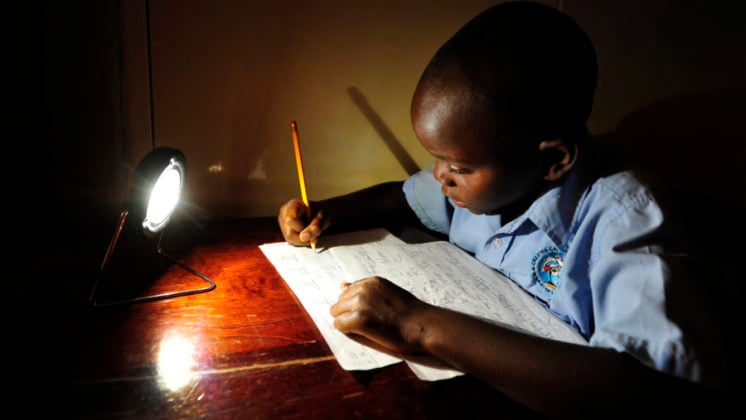

Agbogbloshie is portrayed as the continent’s largest electrical wasteland; in truth it is a functional, profit-making recycling network. The working conditions are harsh and pollution is rife but its inhabitants manage to live, work and save money for their families. There is no question that waste processing in Agbogbloshie has major public health and environmental consequences that need to be addressed by policy designed by the Ghanaian government together with citizens.

Work with informal recyclers, don’t criminalise or dispossess them

Not much in Agbogbloshie qualifies as a best or even adequate practice when it comes to dealing with toxic materials. Most scrap workers use, instead, the practices available to a small-scale recycling industry that functions on very little capital. However, despite its drawbacks, Agbogbloshie plays a key role in Ghana’s massive and thriving repair and re-use economy.

Scrap metals recovered by its businesses are used in manufacturing businesses across Accra, contributing to the kind of “circular economy” to which many more developed nations aspire. Read this essay on informal sector innovation in west Africa for more. Rather than demolish this already functioning circular economy, Ghana’s government could improve on it. Some younger inhabitants report that the work in Agbogbloshie was one of the main factors deterring them from crime and even more precarious modes of survival. This eviction will have huge long term effects.

We suspect the international misrepresentation of the dimension of the e-waste in Agbogbloshie – and its subsequent global notoriety – has contributed to its vulnerability to the kind of evictions seen this weekend. Any attempt to pass off violent dispossession of residents and workers of Agbogbloshie as a necessary step towards an environmental clean-up should be repudiated. Protesting residents have called for an immediate halt to evictions/demolitions, temporary accommodation and compensation.

We take this opportunity to show our solidarity with informal waste pickers and recyclers like those of Agbogbloshie, who create value and constitute the only recycling system of many cities and countries, and should be supported to improve their own working and living conditions, not criminalised and driven from their homes.

Lastly, we appeal to media editors and communicators of international institutions to refrain from showing emotive images from waste processing and recycling sites like Agbogbloshie without providing serious background and analysis of the quality and scope of activities there.