In 1982, a family in the US bought a microwave oven. In 2012, thirty years later, the microwave was still working. In 2017, a young lady purchased an iPhone upgrade and a protective case. Four months later, with a splintered screen from a few bounces on the floor, the same young lady must purchase a new phone.

Author: Anna Kučírková

This anecdote makes a vital point about electronics in this fast-moving technology age: they just don’t make ‘em like they used to. It also raises an important question: what should we do with electronic devices we don’t use anymore? Let’s dive deeper into the problematic issue of e-waste.

What is E-Waste?

Dead electronics are the world’s fastest-growing source of waste, and the United States creates more e-waste than any other country. The toxic materials in electronics, like mercury and lead, can harm people and the environment. Americans recycle about 50,000 dump trucks full of electronics every year.

Just how much e-waste is being created?

Research suggests an estimated 1.5 billion cell phones were purchased in 2017, which is around one for every five people on the planet. Each will ultimately reach the end of its lifespan and become electronic waste. The United Nations found that 44.7 million tons of e-waste was created in 2016, and only 20% of it properly eliminated.

In the United States, there are as many televisions as there are people. That is a lot of electronics that will eventually be reduced to e-waste. And while this technology is most likely changing our lives for the better, electronics often malfunction, and unlike the 30-year-old mixer that refuses to die, new technology breaks more quickly.

Throwing things out instead of repairing them has far-reaching consequences for consumers and the environment.

Electronic Pollution

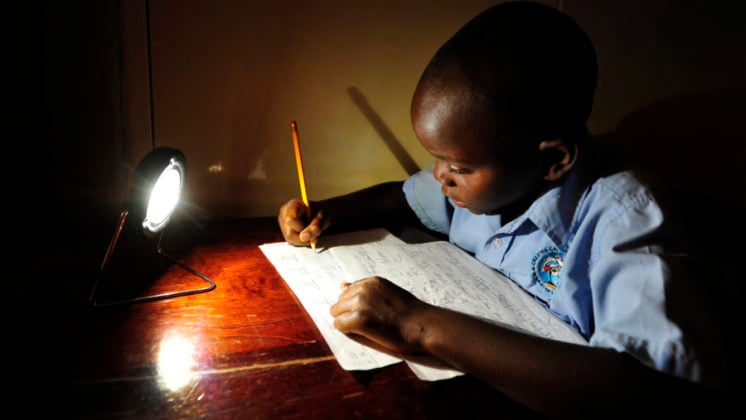

Not only will millions of electronics be purchased each year, they will inevitably create a tide of hazardous “e-waste” that will be dumped illegally in developing countries.

The volume of electronic waste around the globe is projected to grow by 33% in the near future. In recent years, nearly 50 million tons of e-waste was produced worldwide – or nearly 15 pounds per person on earth. This e-waste contains hundreds of different materials and toxic substances like lead, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and flame retardants.

After settling in a landfill, the toxic substances seep into the environment, contaminating land, air, and water. When these devices are dismantled in primitive conditions, people who work there suffer frequently from a range of illnesses.

According to the UN, e-waste is now the world’s most rapidly growing waste source. China generated 11.1 million tons last year and the US 10 million tons.

While exporting castoff goods to poor countries is legal if they can be reused, there are tons of e-waste being sent to Asia or Africa under false pretenses. And no one is keeping track of how much e-waste is actually being spread across the continents.

A study from MIT found that the US only recycled 66% of its millions of discarded computers, monitors, TVs and mobile phones in 2010. The devices not recycled ended up in Hong Kong, Latin American, and the Caribbean.

As newer phone models and other upgraded products are flooding the market, the remainder end up in landfills. These phones are made of precious metals. The circuit boards use gold, copper, beryllium, zinc, and tantalum; the coatings include lead and the batteries are lithium based.

But, less than 10% of phones are being mined for their components. This will eventually lead to shortages of these rare, earth minerals.

Businessmen and manufacturers have recognized the issue and began using tracking systems to gauge how far their e-waste goes. One recycled television, embedded with a satellite tracking device, was bought by a London-based e-waste dealer. That television made a 4,500 mile journey from shipping docks in the UK to the huge Alaba electronics market in Lagos, Nigeria.

The recycling industry has become a haven for e-waste exporters, and thousands of devices end up in developing nations. What cannot be repaired is dumped and people risk their lives picking through the rubbish heaps of electronics in an ever-worsening state of decay.

In Great Britain, nearly 500,000 tons of e-waste goes unaccounted for every year. Great Britain’s e-waste equipment laws place a responsibility on manufacturers to meet the environmental costs of their e-waste. But hazardous waste is being illegally exported as part of an e-waste black market worth millions.

And e-waste isn’t limited to our digital devices. Even so-called green technology adds to the e-waste profile. Solar panels contain toxic metals that can damage the human nervous system, and chromium and cadmium, which are confirmed carcinogens. These toxins are known to leach out of e-waste dumps into water supplies. It may be time for humans to return to the traditional method of repairing broken items instead of replacing them.

Repair, Don’t Replace

In 2013, a group of concerned consumers, environmentalists, recyclers, refurbishers, digital-rights advocates, and repair specialists in the United States teamed up to found Repair.org, working to make sure that when something breaks, US consumers can easily find the information, parts, and technicians they need to repair it.

If an appliance or device breaks, we try to troubleshoot the problem, take the item apart, fix or replace the failed portion, and turn it back on. Unfortunately, repairing computerized products doesn’t have a straightforward path.

Oftentimes it’s easy to recognize that a connection is loose, or a capacitor has burnt out. But, most often, a sophisticated diagnostic is necessary to find the issue. Most manufacturers will not provide help, so every repair becomes trial by error.

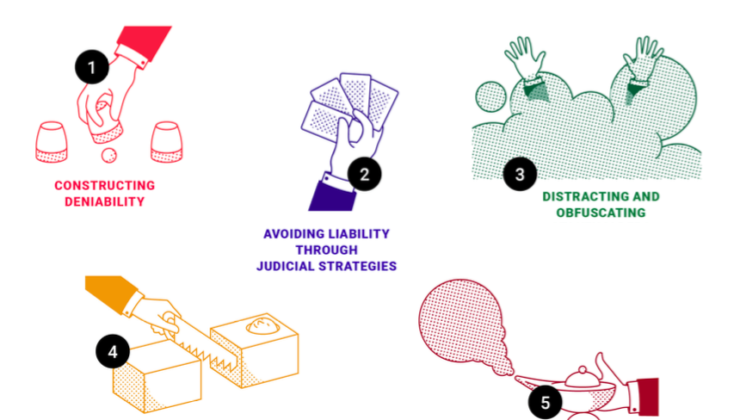

Manufacturers don’t want you to fix your equipment; they want you to purchase a new, fancier upgrade. Some manufacturers even sue people who post repair information online. The only thing they provide is online or phone consultations that cost big bucks. That way, it is simply cheaper for you to buy a new product.

And even if you manage to find the instructions you need, good luck finding the replacement parts. Manufacturers make it so difficult to get the parts, you are better off cannibalizing old equipment that no longer functions.

Some manufacturers would have people believe when it comes to smart watches and mobile phones, repair is impossible. But service centers, using aftermarket parts, are perfectly capable of making small repairs, like replacing cracked screens.

However, any piece of equipment that requires software to run can come with an End User Licensing Agreement. These documents set the rules clearly: You, the owner, can fix anything that doesn’t relate to the software. If you break this rule, your warranty is invalidated, and the company won’t help you with repairs.

So, while repairing should be an option for our digital devices, manufacturers aren’t offering their help. What else can we do to limit e-waste?

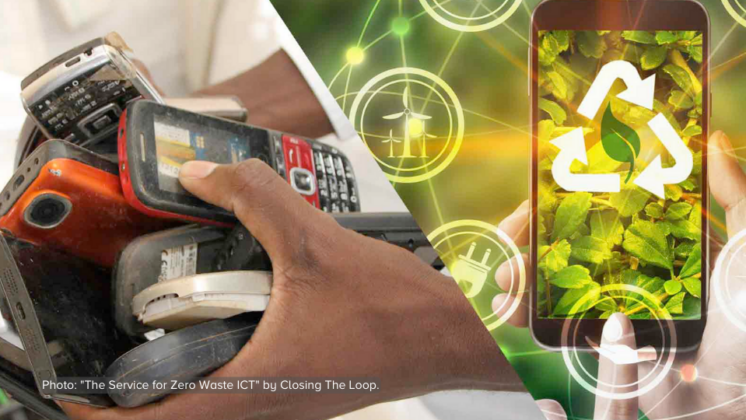

E-Waste Recycling and Mining

Consumers can do something to lower their e-waste footprint. Some of the materials used in creating these products can be recovered and reused, including glass, plastics, and metal.

But, these devices also contain lethal substances like mercury, cadmium, and lead, which must be properly disposed of. When recycling, check your state’s requirements and laws before you prepare to recycle your electronics.

Before handing anything electronic over to a recycler, make sure you completely erase your personal information. But, simply deleting everything isn’t a guarantee. Check with local computer experts about the best ways to scrub your electronics.

Once you are ready to recycle, the process is simple:

- Bring It to the Recycler – check for your local recycling days or retailers that support recycling.

- Donate It – If your gadget still works, there’s probably a charity or nonprofit out there that would be happy to have it.

- Take It to a Tech Firm – lots of manufacturers and retailers offer great recycling programs but read up on them before selecting your recycler.

An alternative to recycling is called e-waste mining, and it is a budding big business.

According to BBC News, “Professor Veena Sahajwalla’s mine in Australia produces gold, silver and copper – and there isn’t a pick-axe in sight. Her urban mine at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) is extracting these materials not from rock, but from electronic gadgets. The Sydney-based expert in materials science reckons her operation will become efficient enough to be making a profit within a couple of years.”

There is research indicating that such facilities could actually be far more profitable than traditional mineral mining. For example, a gold mine can generate five or six grams of the metal per ton of raw material. Up to 350 grams per ton can be mined when the source is discarded electronics.

Traditional mining is labor-intensive; e-waste mining is highly automated. This allows for a cheaper method of extracting the valuable minerals.

Conclusion

Just as human waste can pollute our oceans and air, e-waste can take over landfills, pollute developing nations, and leach toxic chemicals into the earth.

Just as nations have banded together to fight climate change, water pollution, and save endangered species, it is critical that they band together to make a difference in the spread of e-waste.