Electronics workers joined hundreds of thousands of Filipinos who poured into the streets of Manila on September 21 to commemorate the declaration of martial law and to denounce the Philippine government’s corruption of public funds. They also condemned the state violence, mass arrests of protesters, raiding of communities, and killings of bystanders.

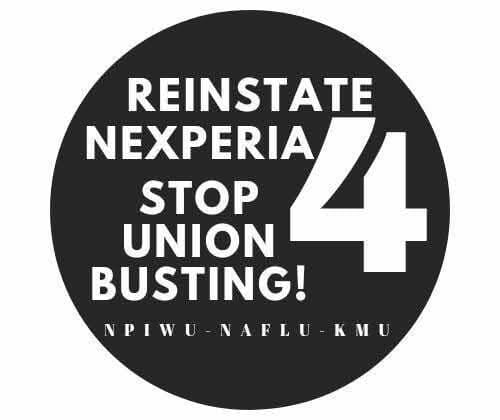

Photo: Workers from Nexperia Workers Union NAFLU-KMU from P.G. Desanjose

Photo: Workers from Nexperia Workers Union NAFLU-KMU from P.G. Desanjose“We are outraged because our hard-earned taxes are funneled into the pockets of corrupt officials,” said Julius Carandang, Secretary of the Metal Workers Alliance of the Philippines (MWAP), and member of GoodElectronics Network. “It hurts even more because apart from our taxes being squandered on substandard or even ghost projects, the profits created by our labor only benefit a few multinational corporations.”

During the Martial Law era (1972–1986), the Marcos regime opened the Philippine economy to greater foreign investment. Electronics was one of the priority industries promoted inside export processing zones (EPZs), such as in Bataan, Cavite, and Laguna. To date, the Philippine semiconductors and electronics industry is the single biggest contributor to the country’s manufacturing sector. It also dominates in terms of manufacturing GVA given its large share in assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP) of semiconductors and other electronic products. OECD reports that semiconductor and electronics products are the country’s biggest exports, and is the ninth-largest chip exporter globally. Industry lobby group SEIPI year-on-year monitoring shows that 58.38% of the total Philippine exports in 2024 are electronics (equivalent to PHP 42.74 billion or USD 763 million).

Despite their critical role in the electronics and semiconductor global value chain, electronic workers continue to face poverty wages, a wide range of health and safety risks, and precarious working conditions. Meanwhile, the average daily wage in the country is just USD8, far from the USD21 national living wage.

Tensions Turn Violent

As the protest in Manila wound down, tension erupted between a group of Gen-Z protesters and police forces manning the barricades. Inspired by recent anti-corruption protests in Nepal and Indonesia, the young demonstrators attempted to dismantle police barriers. The police brutally responded with SWAT teams, truncheons, snipers, and tear gas. Construction worker Eric Saber, on his way home, was gunned down allegedly by the police.

The public condemned the excessive force used to disperse the crowd. According to human rights group Karapatan, at least 277 protesters were arrested, many of them workers and out-of-school youth. Alarmingly, 92 of those detained were minors, with the youngest only nine years old. There are still missing individuals.

Widespread Condemnation

Civil society strongly condemned the crackdown and the police’s brutal and disproportionate use of force, which resulted in the deaths of at least two individuals and left many others injured.

“The violent dispersal on September 21 is a grim reminder of Martial Law’s legacy: corruption, trade union repression, cheap labor and poverty, and human rights violations,” said Kamile Deligiente, Director of the Center for Trade Union and Human Rights (CTUHR), “Instead of addressing corruption and the people’s demands, the government responds with bullets and bloodshed.”

For many Filipino protesters, the September 21 demonstrations underscored the continuing relevance of the peoples’ call: never again to dictatorship, never again to corruption, and never again to the repression of Filipino workers and the people.” #

References:

OECD. (2024). report “Promoting the Growth of the Semiconductor Ecosystem in the Philippines.”

SEIPI. (2024). Philippine Electronics Export Performance December

Rappler. (2025). Analysis: Semiconductor industry expected to perform, investment surge.